Mohs Micrographic Surgery is an advanced technique for treating skin cancer that gives the highest possible cure rate (up to 99%) by removing all of the cancer while leaving the smallest possible scar. Dr. Barlow is a Mohs fellowship trained dermatologist who has performed greater than 10,000 Mohs surgeries and facial reconstructions. You may reference our “before and after” gallery to see some examples of Dr. Barlow’s surgeries.

Mohs micrographic surgery is an outpatient procedure performed in our office; we have an on-site surgical suite and a laboratory for immediate preparation and microscopic examination of tissue. Typically surgery appointments start early in the morning. Most patients spend at least two to four hours in the office but sometimes longer, depending on the extent of the tumor and the amount of reconstruction necessary.

Local anesthesia is administered around the area of the tumor. The use of local anesthesia in Mohs surgery versus general anesthesia provides numerous benefits, including the prevention of lengthy recovery and possible side effects from general anesthesia. After the area has been numbed, then Dr. Barlow removes the visible tumor along with a thin layer of surrounding tissue. This tissue is prepared and put on slides by a technician and examined under a microscope by Dr. Barlow. If there is evidence of cancer, another layer of tissue is taken from the area where the cancer was detected. This ensures that only cancerous tissue is removed during the procedure, minimizing the loss of healthy tissue. These steps are repeated until all samples are free of cancer. While there are always exceptions to the rule, most tumors require 1 to 3 stages for complete removal.

When the surgery is complete, Dr. Barlow will assess the wound and discuss options for ideal functional and cosmetic reconstruction. If reconstruction is necessary, then Dr. Barlow will usually perform reconstructive surgery to repair the area the same day as the tumor removal. Depending on the size of the tumor, depth of roots, and location, one of the following options will be selected:

- Small, simple wounds may be allowed to heal by themselves (process known as secondary-intention healing).

- Slightly larger wounds may be closed with stitches in a side-to-side fashion.

- Larger or more complicated wounds may require a skin graft from another area of the body or a flap which closes the defect with skin adjacent to the wound.

- On rare occasions, the patient may be referred to another reconstructive surgical specialist.

Download our helpful guide, Preparing for Mohs Surgery

For more information, you can visit: skincancermohssurgery.org and mohscollege.org

Before and After:

PHOTO 1. A large basal cell carcinoma of the right temple (A) removed after three stages of Mohs micrographic surgery and repaired with an advancement flap. Here is the early result at six weeks showing temporary redness (B).

PHOTO 2. Two recurrent basal cell carcinomas of the left cheek (A) removed after five stages of Mohs micrographic surgery resulting in two large wounds that were repaired with a rotation flap. Long-term result (B). Photos reproduced with permission, James O. Barlow. Repair of Two Large Adjacent Cheek Wounds. Dermatol Surg 33 (5), 603–606.

PHOTO 3. A basal cell carcinoma of the right temple (A) resected with two stages of Mohs micrographic surgery and repaired with a rhombic flap to avoid distortion of the eyebrow. (B)

PHOTO 4. A ill-defined basal cell carcinoma of the left cheek removed in three stages of Mohs surgery(A) and repaired in a linear fashion. Long-term result (B).

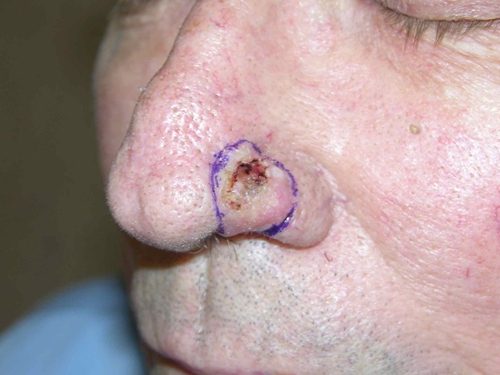

PHOTO 5. A morpheaform basal cell carcinoma of the right nose removed in four stages of Mohs micrographic surgery(A). The wound was repaired by using the skin of the cheek; this is known as a nasolabial transposition flap. Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 6. A recurrent basal cell carcinoma of the right nose required multiple stages of Mohs surgery (A) and the resulting wound required cartilage grafting and a two stage reconstructive surgery (paramedian forehead flap). Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 7. An ill-defined squamous cell carcinoma of the cheek (A) treated with three stages of Mohs micrographic surgery and the resulting defect was repaired using a rhombic flap. Long-term results (B).

PHOTO 8. A large and “pearly” basal cell carcinoma of the nose (A) treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and the resulting defect was repaired using a Reiger flap. Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 9. A sclerotic basal cell carcinoma of the right upper lip (A) removed after four stage of Mohs micrographic surgery. The large defect was repaired along the natural lines of the lip using a “V to Y” flap. Long-term result (B). Photos reproduced with permission, James O. Barlow. The tissue efficiency of common reconstructive design and modification. Dermatol Surg. 2009 Apr;35(4):613-28.

PHOTO 10. A melanoma of the right cheek treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (A) removed after 3 stages of resection. The wound was repaired with a cheek rotation flap, long-term result (B).

PHOTO 11. A squamous cell carcinoma of the edge of the ear (A) removed with two stages of Mohs micrographic surgery. In order to prevent notching of the ear and advancement flap was performed. Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 12. A large rapidly growing squamous cell carcinoma (A) required three stages of Mohs micrographic surgery which greatly weakened the structure of the ear. It required both a cartilage graft and skin graft to restore a normal shape to the ear. Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 13. An ill-defined squamous cell carcinoma (A) took five stages of Mohs micrographic surgery to remove. An advancement flap was used to repair both the skin and muscle of the lip, preserving appearance and function. Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 14. Squamous cell carcinomas can begin on the pink of the lip and spread broadly before they are detected. This skin cancer (A) was removed after four stage of Mohs micrographic surgery and was repaired using the inner skin of the lip (mucosal advancement flap). Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 15. A squamous cell carcinomas involving most of the nostril (A). After Mohs micrographic surgery, the entire nostril was rebuilt using a folded nasolabial transposition flap (Spear’s flap). Long-term result (B).

PHOTO 16. A basal cell carcinoma of the nasal tip (A) after two stages of Mohs micrographic surgery as small wound was left. A bilobed transposition flap was used to preserve the shape of the nose. Long-term result (B). Photos reproduced with permission, James O. Barlow. The tissue efficiency of common reconstructive design and modification. Dermatol Surg. 2009 Apr;35(4):613-28.